One of the most controversial issues surrounding hydraulic fracturing is the risk posed by the activity to human health.

Fracking has been known to lead to to the contamination of local air and drinking water. Substances used in hydraulic fracturing processes have seeped into both groundwater and surface water at various points during the extraction process.

Chemicals in fracking fluids and waste water have been linked to cancer, endocrine disruption and neurological and immune system problem. A Yale University study found that, of the substances for which there is toxicity information available, at least 15% of those substances are toxic to human or aquatic life.

Air pollution from fracking adds to the toll on public health. Emissions are produced from drilling as well as venting and flaring of gas. Construction of well pads and heavy trucking contributes to particulate matter emissions, which aggravate cardiovascular disease and respiratory problems, particularly in children and the elderly. High levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particularly toluene, xylene, and benzene, are found in areas surrounding fracking sites. These compounds are linked to increased rates of birth defects. A 2014 study in Colorado found a direct increase of congenital heart or neural tube defects with proximity of mothers to natural gas extraction sites. Heightened levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are also found near fracking operations and exposure to these compounds increases lifetime cancer risk dramatically.

Both communities located near fracking sites and workers at sites are exposed to these harmful substances. However, fracking also contributes directly to climate change through release of high levels of methane. Globally, climate change has been linked to many public health problems, from spread of vector-borne diseases, to extreme heat waves, and even decreased nutritional content in food crops.

Fracking and Industrial Effluents (a.k.a—produced water)

The chemicals used by oil and gas companies to carry out fracking operations are commonly referred to as “fracking fluids”. There are over 1,000 known ingredients utilized by various oil and gas companies in fracking fluids although generally they are listed as a dozen or so chemicals. These fluids include acids, alcohols, aromatic hydrocarbons, bases, hydrocarbon mixtures, polysaccharides, and surfactants.[1]

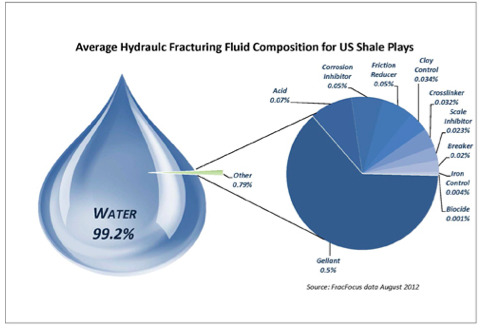

The following chart, provided by Frac Focus, suggests a typical breakdown by percentage of what is contained in fracking fluid.[2]

Image: Fracking fluids by percentage composition. Source: Frac Focus

At first glance we notice that nearly all fracking fluid (99.2%) is presumably water and that only 0.8% are chemical components. The problem is however, that the various chemicals contained in that 0.8 percent and the quantities used is the subject of extremely heated controversy and concern.

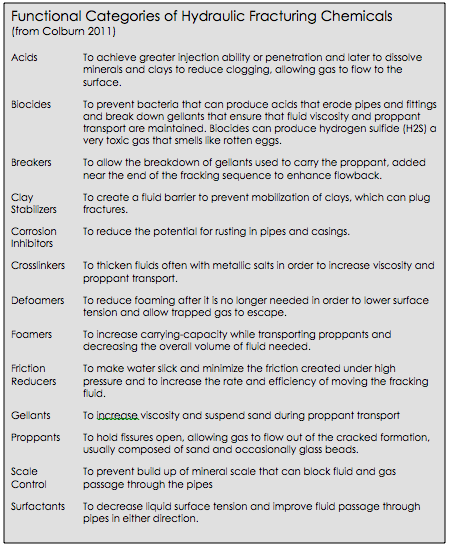

The chemicals used in any given well will vary, depending on the type of soil/geology, water being used, and fossil fuel being extracted. Some of the basic properties of the chemicals used are geared to achieve certain desired results, such as reducing friction and lubricating the extraction areas to ease out the targeted fossil fuel. Other chemicals include biocides to avoid natural decay, and oxygen reducers to avoid the rusting of metal in the piping as well as acids to reduce potential drilling mud damage. Fine sand is also used to wedge open fractures in the geology allowing the fossil fuel to makes its way back up to the surface when placed under pressure.

The following table (Colburn 2011) illustrates some of the more common chemical fluids used (and the reason for their use) in the hydraulic fracturing process.

Image: Fracking fluids and their function. Source: Colburn et.al. 2011.

Public attention, particularly from advocates against fracking, has been extremely concerned with the human health risks of the chemicals found in fracking fluids, largely because of the many documented cases of communities suffering health impacts near fracking operations, but also because the industry has been very secretive over the chemical content in their fracking fluids.

In the United States, the oil and gas sector has stoutly fought against revealing the exact composition of fracking fluids, arguing that the special mix of chemicals utilized in fracking fluids is a trade secret. The problem of course, from a human rights perspective, is the lack of information available to communities about the potential hazards and presence of toxic chemicals in residential environments or where they might compromise community drinking water.

The oil and gas sector often suggests that fracking fluids already amply exist in the public realm (including in ice cream, cheeses and drinks—as argued by Argentina’s State-owned oil and gas company YPF) and that as such there is nothing to fear over their composition or presence in the local environment. They argue that fracking fluids do not contaminate the environment, or that their use is extremely minimal in the fracking process, emphasizing that the amount of fracking fluid utilized per well is under 1% of the total volume of fluids utilized, and that the rest is simply water and as such, there is nothing dangerous about these fluids.

Images (left) and (right): Fracking fluids and container stored at fracking well pad.

see: http://www.marcellus-shale.us/fracking.htm

While it is true that most fracking fluids do already exist in industry and that by percentage they may represent only a few percentage points of the mix, their mere presence in any volume (as opposed to their relative volume in percentages) is what really needs to be considered. As suggested by the United States Department of Energy, in a report published in 2009:

“Most industrial processes use chemicals and almost any chemical can be hazardous in large enough quantities or if not handled properly. Even chemicals that go into our food or drinking water can be hazardous. … the potential exists for unplanned releases [caused by fracking] that could have serious effects on human health and the environment. By the same token, hydraulic fracturing uses a number of chemical additives that could be hazardous … many of these additives are common chemicals which people regularly encounter in everyday life.” (USDOE, 2009)

The fact that fracking fluids may only be 1% by volume in the process of hydraulic fracturing, does not preclude that even small amounts of these elements may not be detrimental, even deadly to human health or to the environment. As Colborn et.al. argue,

“Industry representatives have said there is little cause for concern because of the low concentrations of chemicals used in their operations. Nonetheless, pathways that could deliver chemicals in toxic concentrations at less than one part-per-million are not well studied and many of the chemicals on the list should not be ingested at any concentration. Numerous systems, most notably the endocrine system, are extremely sensitive to very low levels of chemicals, in parts-per-billion or less. The damage may not be evident at the time of exposure but can have unpredictable delayed, life-long effects on individuals and/or their offspring. … Health impairments could remain hidden for decades and span generations.” (Colburn 2011, p.1049).

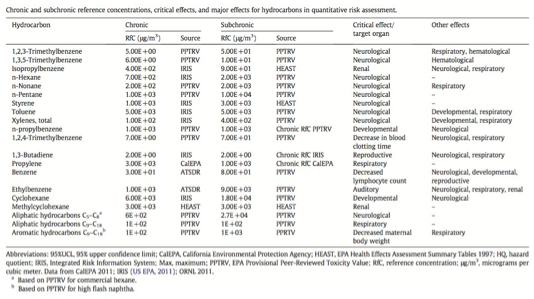

The following table in L.M. McKenzie 2012 lists chronic and subchronic reference concentrations, critical effects and major effects for hydrocarbons in quantitative risk assessments:

Image: Fracking fluids and associated human health impacts. Source: McKenzie 2012.

McKenzie et.al. conclude in their research that “residents living ≤ ½ mile from wells are at greater risk for health effects from natural gas developments than are residents living > ½ mile from wells. Subchronic exposures to air pollutants during well completion activities present the greatest potential for health effects. (McKenzie et.al. p.1)

Finally, Colbron notes that the chemicals utilized in the entire extraction process, including the ‘pre-fracking’ phases of drilling, can impact human health, and not only in the actual fracturing portion of the process. Colbron finds that people have suffered serious health symptoms such as:

“respiratory distress, nausea, and vomiting. From the first day the drill bit is inserted into the ground until the well is competed, toxic materials are introduced into the borehole and returned ton the surface … [and] it has been commonplace to hold these liquids in open evaporation pits until the wells are shut down, which could be up to 25 years.” Colbron 2011. P. 1053.

According to a recent EPA study identifying over 1,000 chemical ingredients among fracking fluids it reviewed, the most common substances found (in 65% of wells) were hydrochloric acid, methanol and hydro-treated light petroleum distillates. Skin exposure to hydrochloric acid can cause irritation and chemical burns. Low exposure to hydrochloric acid fumes can irritate the eyes, nose, throat and mouth; high concentrations can lead to shortness of breath and asphyxia. Ingesting moderate concentrations of methanol can lead to headaches to blurred vision, and high concentrations can lead to blindness, possibly death. If inhaled at certain concentrations, hydro-treated light petroleum distillates can trigger a host of health problems, such as dizziness, headaches and nausea.[3]

The EPA also examined the toxicological properties of hydraulic fracturing chemical additives and found that of the 1,000+ chemicals on record, the potential ‘mobility’ of these chemicals through the environment and the potential for long-term persistence as contaminants were high and that most tend to remain in water.[4]

Considering the accumulative nature of the chemicals used in fracking fluids seepage of fracking fluids into aquifers would result in permanent damage to the water table, a key natural resource for communities and other activities coexisting with fracking. Such contamination can cause obvious health implications for those consuming water polluted by fracking.

Hydrocarbon components such as benzene and toluene and methane that are released during fracking activities can mix with exhaust from equipment creating ground-level ozone. Intake of this ozone can burn lung tissue and cause severe asthma among other chronic health problems.[5]

Few advocacy campaigns focus on the health of workers in the oil and gas sector, although workers at fracking sites may be some of the most directly affected from fracking operations, bearing the brunt of exposure to hazardous chemicals and other components such as sands in utilized in fracking.

[1] source: EPA. June 2015. P. ES11.

[2] see: http://fracfocus.org/water-protection/drilling-usage

[3] see: http://insideclimatenews.org/news/31032015/fracking-companies-keep-10-chemicals-secret-epa-says

[4] EPA. June 2009. P. ES12

[5]http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/fracking/pdfs/Colborn_2011_Natural_Gas_from_a_public_health_perspective.pdf